One reason I bought the Ricoh GR Digital (GRD) was to use as a climbing and mountaineering camera. What follows is a user review and my impressions of the GRD in the mountain environment.

One reason I bought the Ricoh GR Digital (GRD) was to use as a climbing and mountaineering camera. What follows is a user review and my impressions of the GRD in the mountain environment.

I live in Switzerland and mountain trips are frequently on my schedule. A basic day trip involves an elevation gain (and equally large loss) of 800-1200 meters, and involves hiking, rock scrambling or sections of actual climbing. This means that any weight savings makes a difference in terms of how fast and how far I can go on any given trip. It also means that if I want to use a camera, I don’t always have the benefit of using two hands when taking a picture. Sometimes trips just need to be documented, a shot for the blog, or just to record the day. Other times I go with the intention of bringing back some good-looking, printable photos. My current list of cameras includes: Contax G1 (28,45,90mm lenses), Fuji GA645, GA645wi, Minolta 7D.

In general, none of these cameras have been ideal in the mountains, although the Fuji GA cameras come pretty close to being perfect for landscapes. The Contax G1/G2 is a good choice, but if I’m just documenting a trip, then I don’t need or want to go through the costs of processing 35mm film, and then taking the time to scan the images. Plus, while 35mm film can produce some very nice detail and colors, it leaves me wanting more for landscapes. The Fuji GA645 and GA645wi are my favorite film cameras for mountaineering, but (aside from the developing costs) they don’t have a close focusing distance, which only makes them good for landscape shots, and is not ideal for focusing on close objects. The Minolta 7D is great, but generally needs to be accessed from my backpack and can’t be comfortably held with one hand for shooting purposes. Plus, a 7D with lenses is not a light kit to carry into the hills.

From a certain perspective, the Ricoh GRD was seemingly made for mountaineers. The fixed 28mm and 21mm add-on lenses are ideal for landscapes and the camera is incredibly compact. In fact, it’s not a stretch to call the Ricoh GRD (and GRD-II) as well as the GX100/GX200 some of the most compact wide-angle cameras on the market. In addition, the GRD is incredibly light. The Contax G1/G2 is also a compact camera, but it isn’t really light from a pack-weight point of view.

From a certain perspective, the Ricoh GRD was seemingly made for mountaineers. The fixed 28mm and 21mm add-on lenses are ideal for landscapes and the camera is incredibly compact. In fact, it’s not a stretch to call the Ricoh GRD (and GRD-II) as well as the GX100/GX200 some of the most compact wide-angle cameras on the market. In addition, the GRD is incredibly light. The Contax G1/G2 is also a compact camera, but it isn’t really light from a pack-weight point of view.

My first mountain trip with the Ricoh GRD was up Mt. Fuji in Japan, where I also took my Fuji GA645wi. The Ricoh performed wonderfully, but since Mt. Fuji can’t really be considered more than a hike, it wasn’t until I got back to mountaineering in Switzerland that I could get a feeling for how the GRD performs in a mountain touring environment, which is the focus of this article.

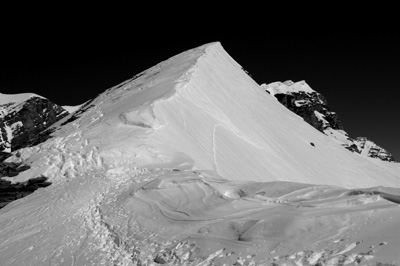

To date, I’ve taken my GRD ice climbing, mountain touring in Graubünden, hiking up Säntis in the Alpstein, and climbing on a klettersteig in Braunwald. I plan on ascending some higher peaks and undertaking some longer tours soon and think the GRD will be up to snuff. There are a few main criteria I’ll be focusing on including how well the GRD can be operated while climbing, it’s attributes such as the LCD screen, and creating good exposures in the mountains.

Operation – One of the GRD’s strengths has always been customization and user control. I can hold the camera up to a scene, automatically see if the histogram looks good, and if not, two small clicks on the exposure compensation button and I know I can take a picture without blowing away the highlights. Similarly, the ISO, focusing mode, file type/size, shutter speed, and aperture can all be changed within a few seconds using one-handed operation. I can’t do that with any other camera I own without the risk of dropping the camera. While seemingly unimportant or at best a convenience for city use, when one hand is holding onto the mountainside, one-handed operation really does make the difference between possibly falling or getting the shot I want. With the GRD I can easily have my left hand secured on a handhold while operating the camera with my right hand.

Operation – One of the GRD’s strengths has always been customization and user control. I can hold the camera up to a scene, automatically see if the histogram looks good, and if not, two small clicks on the exposure compensation button and I know I can take a picture without blowing away the highlights. Similarly, the ISO, focusing mode, file type/size, shutter speed, and aperture can all be changed within a few seconds using one-handed operation. I can’t do that with any other camera I own without the risk of dropping the camera. While seemingly unimportant or at best a convenience for city use, when one hand is holding onto the mountainside, one-handed operation really does make the difference between possibly falling or getting the shot I want. With the GRD I can easily have my left hand secured on a handhold while operating the camera with my right hand.

Image Quality – As a small sensor camera, the Ricoh GR Digital obviously can’t compare with DSLRs or medium format film cameras for image quality. However, you don’t always need a perfect landscape image worthy of pixel-peeping. For trip documenting and small prints, the Ricoh GRD does pretty good. When the images are exposed correctly the contain a great deal of detail and you won’t have a problem creating large prints. Small sensor camera image quality degrades as ISO increases, however, in the mountain environment you generally have more than enough natural sunlight to create exposures with shutter speeds above 1/200 using ISO 64 (the base ISO of the GRD). Since these landscapes will nearly always be with a low ISO, noise won’t be much of an issue. I love the colors I get from GRD files and so long as the images aren’t over-exposed you’ll be pleased with the results.

RAW Write Time – This is by far the greatest drawback of the original GRD. When deciding to buy the GRD, one of the biggest draws was its ability to write RAW files at a time when pretty much every other pocket camera would only do jpeg. Depending on SD card type, the time to write a RAW file is about 9-12 seconds using the original GR Digital. Many users have produced reports detailing which cards write faster, but generally the difference is only a few seconds at best, and the three cards I have all write at different speeds. Depending on your shooting style, for landscape use the RAW write time is sort of irrelevant. With the exception of creating multiple images for stitched panoramas, I haven’t found the long write time to be a significant problem for landscape images. On the other hand, when you’re moving fast over a mountain landscape and trying to document the climb, I would no doubt love the improved RAW write time of the GX100/GX200 and GRD-II, which from what I read are on the order of 4-5 seconds.

RAW Write Time – This is by far the greatest drawback of the original GRD. When deciding to buy the GRD, one of the biggest draws was its ability to write RAW files at a time when pretty much every other pocket camera would only do jpeg. Depending on SD card type, the time to write a RAW file is about 9-12 seconds using the original GR Digital. Many users have produced reports detailing which cards write faster, but generally the difference is only a few seconds at best, and the three cards I have all write at different speeds. Depending on your shooting style, for landscape use the RAW write time is sort of irrelevant. With the exception of creating multiple images for stitched panoramas, I haven’t found the long write time to be a significant problem for landscape images. On the other hand, when you’re moving fast over a mountain landscape and trying to document the climb, I would no doubt love the improved RAW write time of the GX100/GX200 and GRD-II, which from what I read are on the order of 4-5 seconds.

Battery Life – At least with the GRD (not considering the GRD-II as I haven’t used one) the battery life and performance could be better. I find that I’m always getting low by the end of a climb, and although I always carry a second battery, this is one area that I would like to see improvement in. For multi-day trips nothing sucks more than running out of juice, which is one reason I still love my Fuji GA and other film cameras, as I’ve never had a similar battery problem. Cold also seems to be an issue, and hampered by ability to use the GRD while ice climbing during December.

LCD Screen – The LCD screen on the GRD leaves much to be desired in the mountain environment. It just sucks in bright sunlight, and is only good for framing the subject. I do have the external viewfinder, and I’m glad I bought it, but don’t use it very much in the mountains. Since the live histogram is available (and easy to see in sunlight), I’m of the opinion that having a perfect image on the LCD screen isn’t really a big deal. More exact framing can be accomplished with the aid of the external viewfinder. Here’s the thing, If you can monitor the histogram, you know if the highlights will be blown and can adjust the exposure as you like. It doesn’t really matter if you have a bright, perfectly defined image when framing a shot. Often times upon review, the images on the GRD LCD screen look extremely dark in bright sun, but when reviewed later indoors, the images are perfect. As long as you base your exposure on the live histogram, the quality of the image on the LCD is somewhat unimportant. The lack of a live histogram display is one big reason I’ve decided not to buy the Sigma DP-1. The live histogram is invaluable in producing well-exposed images the first time, and eliminates the need to reshoot a scene. It’s one of the things I love about digital cameras to start with, and the primary reason I want live-view in the next DSLR I buy (probably the Sony A900). As the DP-1 lacks this seemingly basic function, I’d rather take a Fuji GA rangefinder on a climb.

Macro Focusing – This is where the GRD really beats all my other cameras and is one big reason why I love climbing with it. You can get as close as 1cm from your subject to create sharp macro images of anything on a tour whenever you feel inspired. You might just think this is great for flower shots – and it is, but what I love is creating wide-angle macro shots during climbing for point-of-view (POV) images. I love getting the Ricoh close to my equipment or looking out over rock edges and creating unique shots that I haven’t seen before. The only way to get similar images with my current equipment is using my Minolta 7 film camera with the Sigma 20mm lens (very close focusing ability), which also is rather large, heavy, and also produces images with just a bit more distortion than I would like. Plus, with the Sigma 20mm you have a much shallower depth of field and a lot of Bokeh (diffused image areas), which isn’t a bad thing, but at the moment for climbing, I like close-up images with a good deal of sharpness across the image. With the small sensor of the GRD, you get really deep depth of field, and combined with the 28mm lens and one-handed operation, this means the ability to take crisp images that are more or less unobtainable with other camera systems.

Macro Focusing – This is where the GRD really beats all my other cameras and is one big reason why I love climbing with it. You can get as close as 1cm from your subject to create sharp macro images of anything on a tour whenever you feel inspired. You might just think this is great for flower shots – and it is, but what I love is creating wide-angle macro shots during climbing for point-of-view (POV) images. I love getting the Ricoh close to my equipment or looking out over rock edges and creating unique shots that I haven’t seen before. The only way to get similar images with my current equipment is using my Minolta 7 film camera with the Sigma 20mm lens (very close focusing ability), which also is rather large, heavy, and also produces images with just a bit more distortion than I would like. Plus, with the Sigma 20mm you have a much shallower depth of field and a lot of Bokeh (diffused image areas), which isn’t a bad thing, but at the moment for climbing, I like close-up images with a good deal of sharpness across the image. With the small sensor of the GRD, you get really deep depth of field, and combined with the 28mm lens and one-handed operation, this means the ability to take crisp images that are more or less unobtainable with other camera systems.

Compact Size – This is one of the main requirements for a mountaineering camera, it needs as small and light as possible. The GRD is great because I can put it in a case and clip it to the chest strap on my backpack. This keeps it away from my carabiners or quick-draws, and is accessible whenever I want to shoot. It also means it won’t interfere with my climbing movements.

Wide Angle Lens – The lens on the GR Digital is very good, as has been reported elsewhere. I have the 21mm add-on lens, which supplements the fixed 28mm lens. The wide angle still sets the Ricoh apart from other compact cameras. Even the top of the line Canon G9 only has about a 37mm (in 35mm terms) lens, which is not ideal for landscapes. Distortion is very low and the lens will render a sharp image across its entire frame. For mountain landscapes, and in particular for climbing, the wide angle lenses on the GRD are unique and much more useful than those of competing cameras. Using the wide lens of the GRD I’ve been able to obtain shots in the mountains that would not have been possible otherwise.

So, Why Do I Take My Ricoh GRD Mountaineering?

Great image quality

Unique macro image ability

Low weight

One-hand operation

Live histogram display

What Needs Improvement?

Battery life

RAW write time

LCD screen performance

Image stabilization would be nice

The strengths far outweigh the drawbacks of the GRD. It remains a high quality, extremely packable digital camera. If you’re in the market for a climbing and mountaineering camera, I highly recommend one of the Ricoh designs, including the GR Digital, GRD2, GX100, and GX200. In addition to using the GRD as a traditional landscape and portrait tool, it also works well for off-camera lighting, and I plan to do more trips packing the GR Digital with a small strobe flash and radio triggers.

Further Reading: